Wind Turbines in Uruguay | earth.org

Each year, the world uses more natural resources than the planet can regenerate, a milestone known as World Overshoot Day. Whilst most countries’ days are “borrowing” resources from the future, Uruguay is pioneering forward, being the closest to staying within ecological boundaries. An unexpected candidate as a developing country with a median population of 37 years old and a stagnating economy, the environment doesn’t seem to be a priority. Though, the Uruguayan government has been committed since 2008 to achieving 98% renewable energy and energy sovereignty. Uruguay is a prime example of how any country, even if it lacks resources, can become ecological and even benefit from the environment.

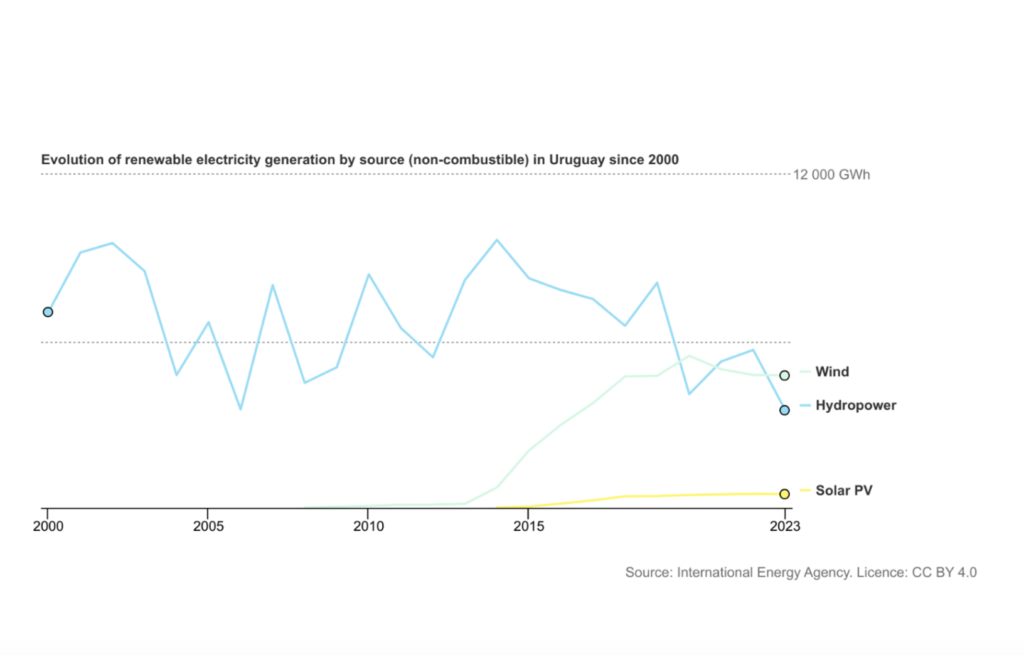

Disaster struck in 2008, when Uruguay experienced a great drought. Hydroelectric dams in the country stopped operating as rivers dried up. Soon, Uruguay was fully dependent on fossil fuels, spending $2.5 billion compared to the average annual $1.1 billion. The growth of the country stopped, exposing Uruguay’s fragility regarding energy dependence. Needing change to avoid an economic collapse, the government had to diversify its energy resources. It had to turn to other sources.

Uruguay’s change was not driven by luck but through policies, thinking long-term. The first incentive came from the National Energy Policy of 2008, which decreed a plan to switch the country to primary renewable energy by 2030. The plan had strict benchmarks, like 50% renewable energy by 2015, leaving no room to delay plans. Furthermore, all political parties in Uruguay agreed to take responsibility for the environment. This collaboration created swifter bills to pass, resulting in Uruguay surpassing the benchmark to 95%.

So what did they do? Uruguay turned to the private sector instead of nationalising. The government kept the wind turbine industry open to investors but remained transparent to build trust between businesses. They provided stability for investors by guaranteeing the price of energy for the next 20 years. Tax breaks were given to companies, and VAT and import taxes were reduced for investors, creating lower up-front costs to build the turbines. The reduction in financial risk and predictability encouraged companies to invest. This resulted in a huge success for the government’s plans, producing 2,500 MW of energy without major investment from the government itself.

Another cornerstone of the plan was the recreation of transport in Uruguay. The government wanted to turn all vehicles, public or private, into electric. This was achieved by subsidising the electric car market. They built a nationwide link of chargers to make electric cars viable rather than just desirable. By doing this, there were great reductions in the cost of fuel for electric cars, being 20 times cheaper, causing a large rise in demand and tripling the units bought in 2024 of battery-electric vehicles. Furthermore, in the main cities, such as Montevideo, public transport has been transformed to reduce emissions. This was done by swapping the whole bus fleet from diesel to electric and linking the buses directly to the renewable energy grid. These adaptations display how even small countries can quickly switch a niche market into a national standard.

The last element of Uruguayan success was agriculture. Farming and cattle were vital to the economy, containing more cows than people in the country. In efforts to reduce methane emissions, all cattle in the country had to be tagged and tracked. In doing this, farmers were kept accountable for sustainable practices. It also gave the government figures on how much pollution was entering the environment, which meant they could target reduction strategies. These strategies included rotational grazing and testing foods other than soy, like high-protein legumes, to reduce the production of methane per kilo of beef. By being more transparent to buyers, it increased the price of cows, as Uruguayan farmers could now label their food as green and organic. This greater investment into the industry meant farmers could now recycle their profits into more sustainable farms.

Though did all of this investment into sustainability hold back the economy? No. Uruguayan investment didn’t cause the economy to slow down but rather propelled it forward. By transitioning the energy sector, modernising transport, and revolutionising farming, the nation has reduced emissions whilst creating jobs and infrastructure. Small or large, developed or developing, Uruguay shows the environment is not a burden on the government but an opportunity for prosperity.